“If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

I keep this quote on my homepage because it captures something fundamental about leading people: it’s not about the mechanics, it’s about connection. Recently I stumbled upon a concept from psychoanalysis that gave me a new lens to think about this, and I want to share it because it maps surprisingly well onto the challenges we face as leaders of people.

The concept: Elasticity of Technique

In 1928, Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi published a paper called “The Elasticity of Psychoanalytic Technique” (Elasticidade da técnica psicanalítica). Ferenczi was a close collaborator of Freud, but he pushed psychoanalysis in a direction that Freud wasn’t entirely comfortable with.

His core argument was simple but radical: it’s not the patient who should adapt to the method, but the method that should adapt to the patient. The analyst needs elastic flexibility to meet each person where they are, instead of forcing everyone into a one-size-fits-all technique.

Ferenczi described the analyst’s work as being like an elastic band — you yield to the patient’s tendencies without ever abandoning the pull in the direction you consider appropriate for progress. The work becomes what he called a “perpetual oscillation” between three things: feeling-with (Einfühlung — empathy), self-observation, and judgment.

What really caught my attention were the two failure modes he identified. They feel incredibly familiar to anyone who has managed people.

The two ways we fail

Interpretation Fanaticism

Ferenczi warned that being sparing with interpretations is one of the most important rules of analysis, and that “interpretation fanaticism” is among the analyst’s “childhood diseases” — a phase that new analysts go through where they’re so excited about their theoretical knowledge that they see unconscious meaning everywhere and can’t resist pointing it out.

Think about this in leadership terms. We’ve all seen this manager, maybe we’ve been this manager: the one who read one management book and now sees “fixed mindset” or “lack of ownership” in every interaction. Every 1:1 becomes a coaching session whether it’s needed or not. Every performance dip gets a diagnosis delivered with confidence. The feedback is frequent, but nothing changes — because the interpretations aren’t landing, they’re just bouncing off people who feel analyzed rather than heard.

Reckless Empathy

The opposite failure: the leader who “feels with” their reports so deeply that they can’t hold boundaries. They can’t deliver hard truths. They avoid conflict. They absorb their team’s anxiety without processing it. They let deadlines slip because someone is going through a hard time — indefinitely. Confrontation feels like betrayal, so dysfunction gets enabled in the name of empathy.

Ferenczi himself was radically honest about this tension. He admitted that during thirty years of practice, he had violated the principle of abstinence in every possible way — extending sessions, not charging sometimes. And then he asked himself the hard question: “am I inflicting more suffering on the patient than is absolutely necessary?”

Building the balance

So how do we find that elastic middle ground? Here are some practical approaches I’ve been thinking about, connecting Ferenczi’s insights with modern leadership frameworks.

Develop your own “analysis”

Ferenczi insisted that the only reliable foundation for good technique is the analyst’s own completed analysis. In a well-analyzed analyst, the processes of empathy and evaluation operate at a conscious level, not from blind spots.

For leaders, this means: you need a practice of self-examination that isn’t optional. This could be therapy, executive coaching, a peer group, journaling — but something where you regularly examine your own patterns and triggers. Without this, you’re running on autopilot and calling it intuition. You can’t hold space for others’ reactions if you haven’t been willing to sit with your own.

Practice the elastic band

Ferenczi’s image: yield to the person’s tendencies without abandoning the pull in your direction. In practice this means when someone on your team is struggling, your first move is to feel with them — not fix, not diagnose. But you don’t let go of what you know they need to do. You hold both. The tension is the point. If it feels comfortable, you’ve probably collapsed into one side or the other.

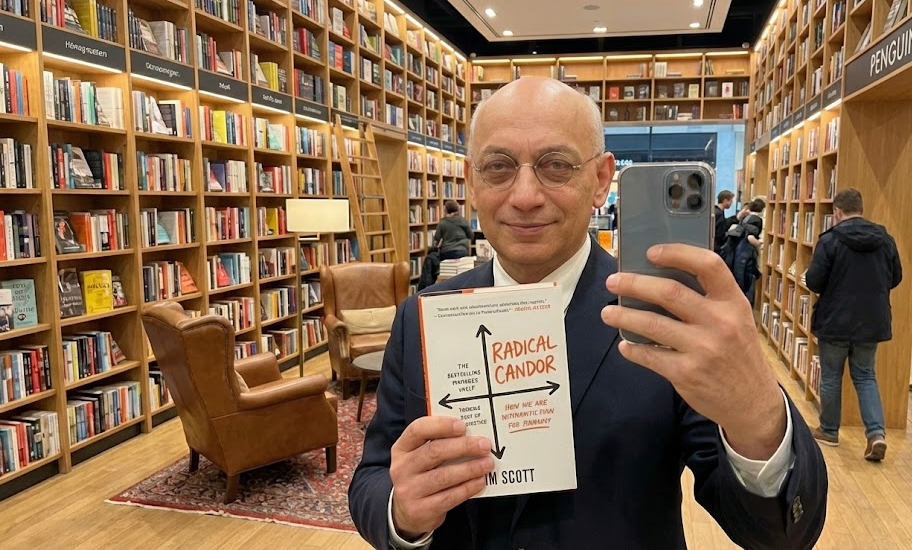

Kim Scott‘s Radical Candor framework captures this well with two axes: Care Personally and Challenge Directly. What she calls “Ruinous Empathy” — high care, no challenge — is Ferenczi’s reckless empathy in a leadership skin. And “Obnoxious Aggression” — high challenge, no care — is interpretation fanaticism stripped of empathy. The sweet spot requires both simultaneously.

Some of her practical advice maps directly to Ferenczi’s oscillation: solicit feedback first (show you can take it before you give it), give brief private criticism in the moment rather than saving it for formal reviews, and always pay attention to how your words land.

Be parsimonious with interpretations

This is Ferenczi’s most underrated advice. In leadership terms: you don’t need to name everything you see. Not every observation needs to become feedback. Not every pattern needs to be pointed out. The question isn’t “is this true?” but “is this the moment, and am I the right person, and will saying this serve them or serve my need to feel perceptive?”

A practical rule: before delivering an insight to someone, ask yourself — am I saying this because they need to hear it, or because I need to say it?

Watch for the childhood diseases

Ferenczi called interpretation fanaticism a childhood disease because it’s a phase. Leaders have their own version. New managers often over-coach. Someone who just learned about “psychological safety” starts diagnosing its absence in every meeting.

The signal: if you’re excited about the insight you’re about to deliver, slow down. Excitement about your own interpretation is often a warning sign that you’re serving yourself, not them.

Monitoring for the lack of balance

The tricky thing about these failure modes is that they feel like the right thing while you’re in them. The interpretation fanatic thinks they’re being helpful. The recklessly empathetic leader thinks they’re being kind. So how do you catch yourself?

Signs you’ve tipped into interpretation fanaticism

- Your reports seem guarded or defensive in 1:1s

- You prepare feedback before the conversation starts

- People stop bringing you problems because every problem becomes a “development opportunity”

- You catch yourself saying “what I’m hearing is…” more than you’re asking genuine questions

- Your feedback is frequent but nothing changes

Signs you’ve tipped into reckless empathy

- You feel emotionally drained after 1:1s

- You keep making exceptions “just this once” — repeatedly

- You know something needs to be said but keep finding reasons to wait

- Other team members show frustration about a colleague you’ve been “understanding” with

- You’ve been carrying information about someone’s struggle for weeks without acting on it

The meta-signal

Ask your team directly. Scott suggests having a go-to question. Hers is: “What could I do or stop doing that would make it easier to work with me?” If people can’t answer that, you’ve probably been operating in one extreme long enough that they don’t trust the question.

Ronald Heifetz‘s Adaptive Leadership framework offers another useful metaphor here: the “balcony and dance floor.” You can’t only be on the dance floor — so immersed in the emotional experience that you lose perspective. And you can’t only be on the balcony — so busy analyzing patterns from above that you’ve lost contact with reality. In any given interaction, notice where you are.

The core principle

Ferenczi’s deepest insight for leaders is this: the technique must adapt to the person, not the person to the technique. Some people on your team need more challenge and less empathy right now. Others need the reverse. The same person needs different things at different times.

The “elastic” leader reads the situation and adjusts — not from a formula, but from a developed capacity to oscillate between feeling-with, self-observation, and judgment.

That’s the balance. And the uncomfortable truth is that it’s never stable — it’s a continuous practice of noticing when you’ve drifted and pulling back.

If you forget everything else from above, remember just one thing: before you speak, ask yourself whether you’re serving them or serving your need to feel like a good leader.

Happy leading! 🎯😁

References

- Ferenczi, S. (1928). A elasticidade da técnica psicanalítica. In Obras completas vol. IV. Martins Fontes.

- Scott, K. (2017). Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity. St. Martin’s Press.

- Heifetz, R. (1994). Leadership Without Easy Answers. Harvard University Press.

- Gondar, J. (2020). Psicanálise on line e elasticidade da técnica. Cadernos de Psicanálise, CPRJ.

- Coelho Junior, N. (2004). Ferenczi e a experiência da Einfühlung. Ágora, SciELO.